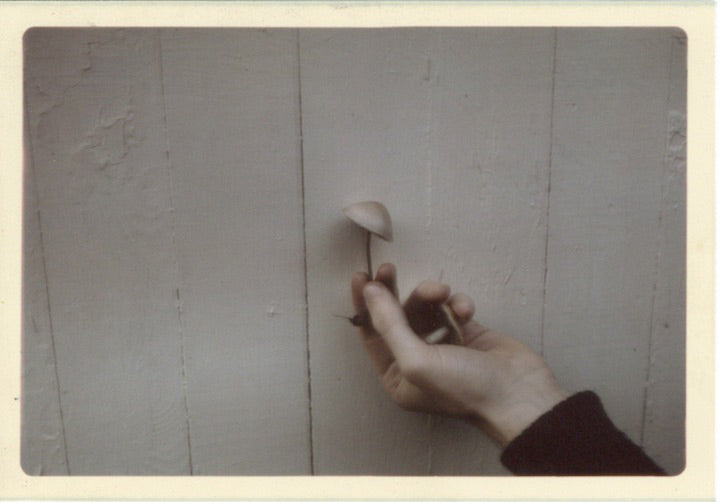

John Cage with a Grenoble Mushroom. Photographed by James Klotsky in 1971.

John Cage's Musical Mycology

by Diana Welch

Revered for the innovative, creative imprint he left on the worlds of music, dance and art, the renowned avant-garde composer, writer, and philosopher John Cage was also deeply immersed in the world of the mycelium. It should come as no surprise that, much like his beloved mushroom, John Cage’s influence is far reaching, even today.

Though he died in 1992 at the age of 79, so much of Cage’s work still feels new and exciting. It makes sense, then, that Cage preferred to describe himself as an inventor, rather than a composer.

He is perhaps best known for his 1952 composition 4’33”. The piece, which might be more accurately described as a work of decomposition, transformed the very concept of music by shifting the focus from what the musician plays, to what the audience hears. Written for any instrument or combination of instruments, the score instructs performers not to play their instruments during the entire duration of the piece, which lasts four minutes and 33 seconds (hence the piece’s title). Though it is commonly perceived as four minutes thirty-three seconds of silence in three movements, the piece actually consists of the environmental sounds that the listeners hear during the performance.

In an essay entitled “Music Lover’s Field Companion,” Cage reflects on the intersection between 4’22” and his time spent mushroom hunting. “I have spent many pleasant hours in the woods conducting performances of my silent piece...” he writes. “At one performance, I passed the first movement by attempting the identification of a mushroom which remained successfully unidentified. The second movement was extremely dramatic, beginning with the sounds of a buck and a doe leaping up to within ten feet of my rocky podium...”

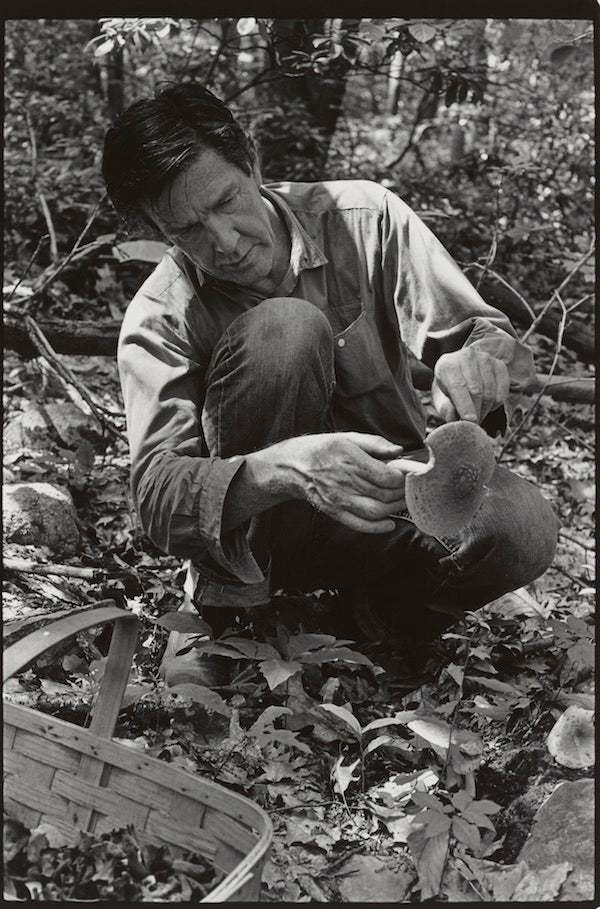

John Cage Foraging in Stony Point, NY. Photographed by William Gedney, 1965.

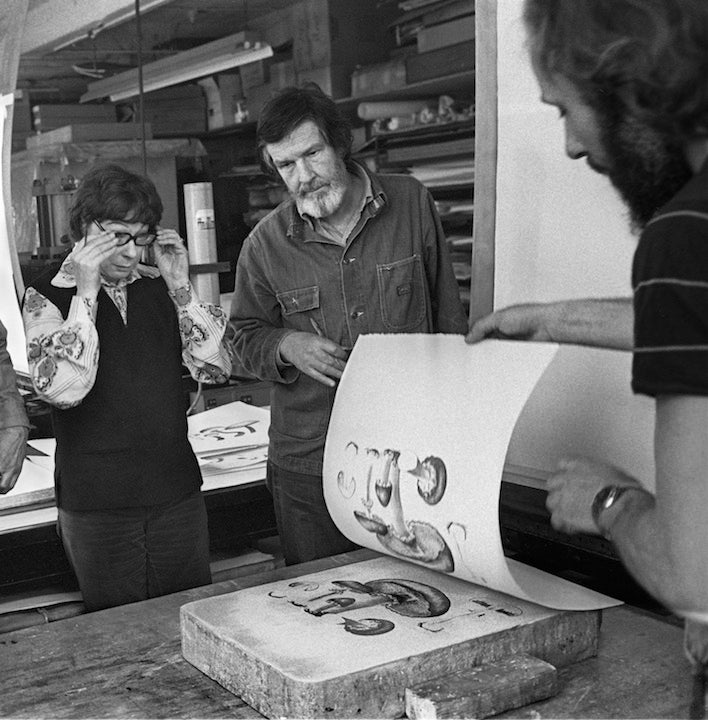

In 1959, Cage began teaching a mushroom identification class at the New School for Social Research in New York. These classes (consisting of five field trips out of the city and into the woods) were in addition to his regular courses in musical composition. They drew parallels between the powers of observation and the art of listening. “If you run into people who are really interested in hearing sounds,” said Cage, “you’re apt to find them fascinated by the quiet ones. ‘Did you hear that?’ they will say.”

"Each One is itself.

Each mushroom is what it is,

its own center."

Heavily influenced by the Japanese Buddhist scholar Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Cage regarded silence as a kind of openness, a receptivity to the Self and its surroundings which, in the Zen tradition, are viewed as one and the same. Though he was famously reluctant to discuss whether or not his practice of Zen Buddhism directly influenced his work, Cage seemed quick to acknowledge how his myclelial hobby guided him in his Zen practice. “Each one is itself,” he explained. “Each mushroom is what it is, its own center. It’s useless to pretend to know mushrooms. They escape your erudition.”

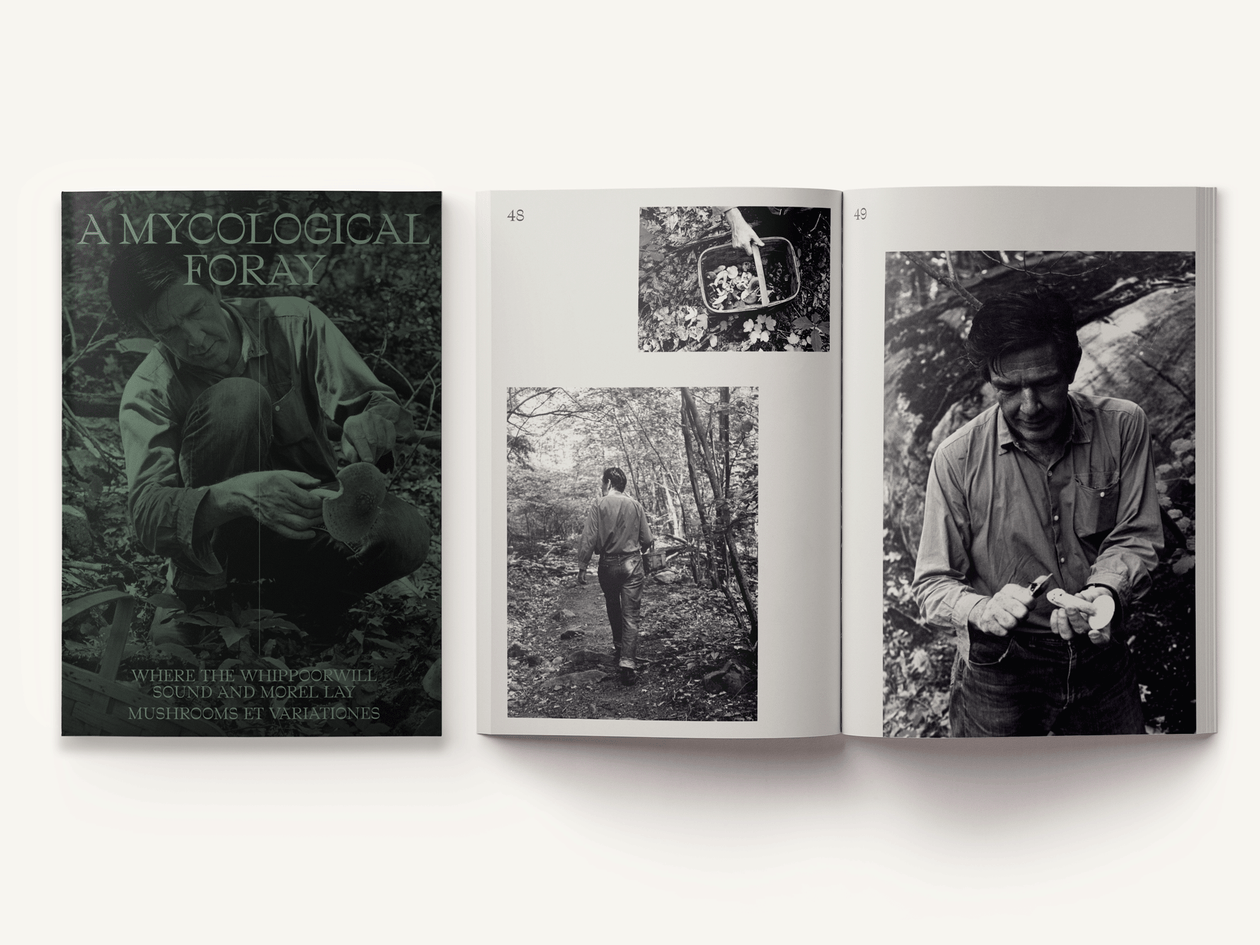

These musings — along with essays, diary entries, photographs, drawings, and transcribed music compositions — are exquisitely detailed in the new monograph from Atelier Editions, John Cage: A Mycological Foray - Variations on Mushrooms. Having sold out completely when it was first published in June 2020, the publisher will be printing another, final run in the Spring of 2022.

No matter the time in which it was created, so much of Cage’s work still holds a kind of transformative power. Take, for instance, his “Prepared Piano” which he invented by placing objects beneath and between the strings of a grand piano, creating completely new sounds associated with the keys. He then used this entirely new instrument in his piece “Sonatas and Interludes” — a work that was first performed in 1946.

"If you run into people

who are really interested in hearing sounds,

you’re apt to find them fascinated by the quiet ones.

‘Did you hear that?’ they will say.”

Today, anyone can explore Cage’s innovation through a decidedly more modern lens: an App called CagePiano, which allows the user to mess around with 36 of the “prepared” notes, all lovingly captured and sampled by the John Cage Trust. The compositions created using the combined sounds of these new notes can even be recorded and shared via social media or email — a connective technique that Cage would have surely enjoyed seeing bear fruit.

John Cage: A Mycelogical Foray — Variations on Mushrooms is out now from Atelier Editions.